Hello friends!

I’m so pleased to share another installment of the occasional series I do, in which I invite an author to tell us five things—not only about their most recent book, but about their life too.

I first fell in love with Pam Houston decades ago, when, as an undergraduate in a fiction writing workshop at the University of Minnesota, I read her story “How To Talk to a Hunter,” in the Best American Short Stories 1990. Gobsmacked is the word that comes to mind to describe how I felt when I met this bold, smart, funny, brave, strong woman on the page. She immediately became a guiding literary light to me. Years later, when we started appearing on literary panels and teaching at writing workshops alongside one another, I had the opportunity to to tell her as much, and once I finished with my fangirling, we became dear friends.

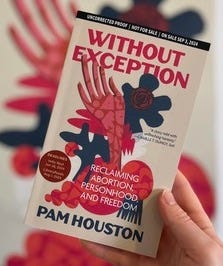

Her new book, Without Exception, is classic Pam Houston. Unflinchingly honest, wildly compassionate, and fearless in the questions it asks and seeks to answer. It’s a book about reproductive freedom and bodily autonomy that’s part memoir, part call to action, part history of abortion rights in the United States. I read it with a racing heart, not only because (sadly) the subject is so timely, but because Pam writes about it all just so damn powerfully.

It’s a riveting, must-read and, lucky us, her publisher is offering a special discount. You can buy it at the Torrey House Store and use the code FREEDOM at checkout for 15% off your purchase. I hope you enjoy the beautiful words she shares with us here, in my interview with her.

xCheryl

Tell us about a time when you took advice that turned out to be really good or really bad.

I had a really rough time with Covid and an even worse time with long Covid. I lost nearly a whole year of my life and though I am much better now I still have some lingering symptoms. This was in 2020 and Western doctors didn’t even want to talk to me, but an acupuncturist in Santa Fe named Alix Bjorklund saved my life. About half way through the year, when things were a bit better but my kidneys just couldn’t get well, Alix told me to go home and find a reason to live before the day was out. I pulled into the driveway of the house I was renting in Santa Fe so that I could see Alix three times a week, walked inside, opened my computer and with what seemed like zero forethought and dwindling savings, booked a 250 kilometer, seven-day ride on Icelandic Horses to a place called Landmannalaugar one year from that day, figuring that by then, I would either be better or dead.

I wasn’t dead, but I was still weak and exhausted when I flew to Iceland to make that ride. It was the best and among the hardest seven days of my life, which before Covid had been pretty great and full of good health and adventures. Those horses taught me, not only that I could fly again, but that I could trust the world again. It opened up pathways of complex cross species communication, a thing I had been dabbling with all my life, but after that trip committed to wholeheartedly in the form of the new book I have begun writing.

There is photo of me from that trip I look at these days whenever I have to make a big decision. Dirt all over my face, I am exhausted from a long day of tolting and galloping in the rain, but my eyes tell me I am as sure as I have ever been in my life that I am in exactly the place I am supposed to be.

Tell us about a personal transformation in your life or a change that you’ve made for the better.

Twelve years ago this January, I was asked to fill in for another writer at the last minute, teaching for a few days at the Institute of American Indian Arts MFA program in Santa Fe. I was asked because I was within driving distance of Santa Fe and because I am not afraid to drive in a blizzard, and not because I had any particular experience with any Native Nation. But I liked everyone I met there tremendously, and most of them liked me, so I was invited to be a contracted member of the faculty. I had to quit another job to do it, a job I liked, but something in me understood that working with the faculty and students at IAIA was going to be one of the most important and most transformative decisions of my life.

At IAIA I have received an education like no other. I have learned about my country and all its inequities, all its white supremacies. All the childish notions about US exceptionalism have been revealed to me for what they are. I have seen up close what 500 years of genocide and generational trauma has wrought, and I have seen deep healing in action, through the arts, and through community and compassion and a world view that sees all beings—all beings—as sentient and valuable.

Mostly I have learned better how to bear witness, how not to try to fix but to hold space for. I have learned to shut my mouth and wait for those who have been silenced by fear to speak. I have also been invited into the warmth of so many communities, so many homes. I have been forgiven when I have misstepped, mostly. I have learned how to earn trust, not across the board and not whole cloth, but just enough that I can be of some value to these amazing books coming into the world. I have learned about Native Futurism, who’s Earth-centric values are the only values possible if there is to be a future at all. I have been invited to practice allyship, and I am not perfect at it, but I am always working to be better. It has been the most valuable work of my life.

Tell us about your new book, Without Exception.

In the summer of 2022, when the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision put an end to forty-nine years, five months and two days of Roe V Wade and gave the government control over what a woman does and does not do with her body, I realized that my reproductive life corresponded precisely with Roe’s lifespan. I got my first period in 1973, the same month the Supreme Court ruled on the case Jane Roe and a doctor brought to them concerning a woman’s right to privacy, and I was just at the fully into menopause moment as Dobbs came down the pike. I mentioned this to my editor at Torrey House and without a moment’s pause she said, “Do you want to write a book about that for the 2024 election?” And I said “I guess I do.”

Writing this book seemed like the best way for me to use both my particular skill set and my particular history to help get out the vote. I was sexually abused by my father throughout most of my childhood. Had I become pregnant during that time and been forced to carry that baby to term, I think I would have ended my life. The particular cruelty of abortions bans that have no exception for rape or incest, no exceptions for endangerment to the life of the mother, reveal these laws for what they are, an attempt to keep women down, to keep them poor and overburdened, to eliminate all possibility they might have time to organize, to run for office, to help make a world where everyone can thrive. It is my belief that if women could ever, collectively, make a decision to drop the cloak of imposed shame that we have been encased in forever, there would be no stopping us, and we might never have another male president again.

I wanted the book to be multifaceted and multi-voiced. I do include my own history with abortion as well as what I know of my mother’s, but the book also contains a song written about abortion by a young singer-songwriter team called The Montvales, a formal poem on the hypocrisies of Catholicism written by Jen Simon, one of my students, the language of several studies done by the University of San Francisco including the Turn Away Study, and the Post Roe Study and excerpts from Sonia Sotomayor’s moving dissent. Like all books, Without Exception is also about language, the language we have agreed to use as a culture to give men an infantile and simplistic power, and the language we use to keep women in their place.

Besides the book’s number one goal of getting out the vote in 2024, it is also my hope that it will get women talking to each other more and more about their abortions (it is certainly working among my friends and fans so far), that we might take some of the shame out of this procedure that one third of women will have at least once in their lifetime, that we will treat each other with grace and mercy, and help each other to be free.

Tell us about a regret you have or a mistake you’ve made.

The two main categories of regrets in my life are men and ranch-sitters, but I have made up for those lately with one really good man and a whole lot of great ranch-sitters, so I don’t think those are worth talking about. I also try not to spend a lot of time with regret. I’m ready with an apology, ready to try to make up for whatever I have done wrong, but I am not a wallower and never have been.

One serious regret of my life is that I have not become fluent in a second language. I speak a little French, and I am trying to learn Icelandic, just because of how much I love the horses and the country and the Icelandic people. But Icelandic is hard, and most of the Icelanders prefer I don’t even try. I would have liked to live in another country too, for a few years, though I have been lucky enough to visit many places for extended periods. I have spent my life searching for home and I thought I had found it those 30 years in Creede until the Trumpers took over the county. If we get democracy saved in November, I might get serious about spending at least a year or two elsewhere and becoming at least passable in the language of that place, and if we don’t…well if we don’t, I guess I will learn the language of whatever country lets me in.

Tell us your best advice.

My best advice might sound like it only applies to writing, but I mean it to apply not only to writing but also to life. It is “trust the metaphor, it knows more than you do.” As you can see in Without Exception, my writing process involves paying strict attention to the metaphors the world offers me, and bringing them together in odd combinations to make my stories. The Mother of the Forest in Big Trees Calaveras State Park, the American Flag made out of twinkly lights that covers one side of my neighbor’s house, the first summer in twenty years that we had enough rain, and therefore no fire danger, and therefore more wildflowers than I ever remember in the pasture behind my barn, these are all metaphors that are central to Without Exception.

But trusting the metaphor extends beyond writing to trusting the signs we are given about how to live our lives. If I can’t stop laughing every time I get to gallop an Icelandic horse across a meadow, this means I should ride Icelandic horses absolutely as much as possible. If I feel small and shamed every time I get together with a particular friend, it may be evidence that the friendship ended some time ago without my exactly knowing it. Mother Earth gives us warning signs daily now, about all the ways we have mistreated her in the form of hurricanes and floods and fires and disease, and we fail to pay attention at our own peril.

Trusting the metaphor means to me flowing with the current of events rather than against it. While writing, sometimes I feel as though I have jumped into some magical river of collective unconscious (you might call this spirit, or even God(ess)) and for a minute, or sometimes even an hour, it carries me along from idea to idea to revelation. Sometimes, if I am really lucky, life feels like that too.

Pam Houston is the author of the recently published, Without Exception: Reclaiming Abortion, Personhood and Freedom, the memoir Deep Creek: Finding Hope In The High Country, as well as two novels, Contents May Have Shifted and Sight Hound, two collections of short stories, Cowboys Are My Weakness and Waltzing the Cat, and a collection of essays, A Little More About Me, as well as a book of essay between Pam and environmental activist Amy Irvine, called Air Mail: Letters of Politics, Pandemics and Place. Her stories have been selected for volumes of The O. Henry Awards, The Pushcart Prize, Best American Travel Writing, and Best American Short Stories of the Century among other anthologies. She is the winner of the Western States Book Award, the WILLA Award for contemporary fiction, the Evil Companions Literary Award and several teaching awards. She teaches in the Low Rez MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts, is Professor of English at UC Davis, and co-founder and creative director of the literary nonprofit Writing By Writers, which puts on between seven and ten writers gatherings per year in places as diverse as Boulder, Colorado, Tomales Bay, California and Chamonix, France.

Pam’s passions include Icelandic Horses (especially the ones who live in Iceland, where she goes as often as possible), Irish Wolfhounds, travel, mentoring and teaching, particularly teaching writing about the more than the human world. She lives on a homestead at 9,000 feet near the headwaters of the Rio Grande in Colorado with her husband Mike and two dogs, a quarter horse, a miniature donkey, four Icelandic ewes, four hens and a rooster.

Trust the metaphor, trust the signs from the universe… this helps me. Thank you.

I could not love this more.

Thank you both for opening my heart tonight.