Hello friends,

I’m so pleased to share another installment of the occasional series I do, in which I invite an author to tell us five things—not only about their most recent book, but about their life too.

I first discovered Chelsea Bieker’s work a few years ago when I was culling the bookshelves in my bedroom and came upon a glittering gold copy of her debut novel, Godshot. I didn’t know how the book came to be in my bedroom, but there it was and when I opened it and began reading, I was utterly hooked. Chelsea lives in Portland, like me, but we’ve never met, so I’m nothing but a fan of her wise, fierce, perceptive, electric prose.

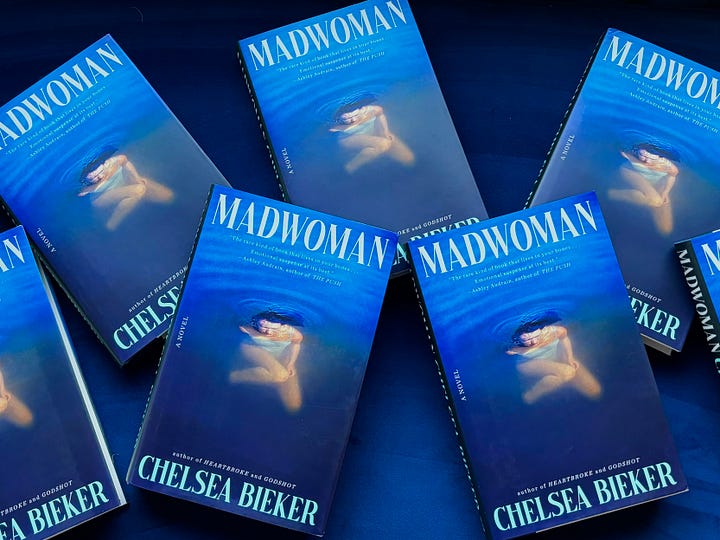

That fandom deepened when I read her new novel, Madwoman, which is out today. It’s a gripping, gritty, gorgeous book about motherhood, the traumas of domestic violence, and the mad, raw, funny, wrenching, astonishing things we do to survive, or, as Chelsea puts it in her beautiful interview, about “facing the darkest parts of yourself to finally be free.” This book made me laugh and cry. It reads like a thriller and a love song. It’s about being crushed and rising strong. I hope you’ll get your hands on it as soon as possible, or go out and see Chelsea at one of the stops on her book tour, which you can read about on her Substack.

Happy pub day, Chelsea!

xCheryl

Tell us about a time when you took advice that turned out to be really good or really bad.

I’ve always been interested in psychology and somatic healing modalities, and after I got my creative writing degree at twenty-five, I pretty quickly started researching counseling psychology programs. I felt excited about this potential viable career path with more stability than fiction writing and the unstable adjunct teaching I’d fallen into, and, perhaps more true, was that I was comforted by the idea of staying in school longer, school having always been a safe place. But then a close friend offered some straight talk advice I was not asking for. She told me she was worried if I jumped right into this other area of study, that I wouldn’t write fiction anymore, and she really, really wanted me to keep writing.

I think in the moment, I was taken aback because instead I could only hear that she didn’t think I should become a therapist. I felt hurt, and like she wasn’t seeing me. I explained that I felt strongly I could keep writing fiction and do this (pretty grueling) new degree program at the same time, but after the days wore on and my first giant payment was due for the program, I couldn’t get her words out of my head. Slowly, I began to see that actually, she just really believed in my talent want to see me put something major in front of it before I gave myself a chance. She was seeing me as…a writer. And maybe also she saw that I wasn’t ready to be a therapist in the traditional sense (I wasn’t!).

Days after turning down my acceptance, I was awarded a residency at MacDowell, a total shock to me. I went there for six weeks and wrote a first draft of what would become my first novel (something I couldn’t have done so swiftly if I was in that program), met some lifelong soulmate type friends there, one of which is still in my writing group today, had a baby, and lived a lot of life. My interest in psychology and healing hasn’t faded a bit and I’ve continued to explore it on my own terms, and I hope one day I’ll study it in an official capacity, but I’m glad I did what seemed to be the riskier choice at the time by not jumping right into the next thing. Sitting in the discomfort of the unknown, leaning into being a writer. I think in some ways it was a defining moment, having another person dig their heels in for me. I’m glad I was able to receive that, and that she saw me as an artist first and foremost. It was a tremendously powerful lesson in the importance of having friendships that contain that sort of love-based honesty. It was also a lesson in listening both to another, and to myself and parsing out the truth.

Tell us about a personal transformation in your life or a change that you’ve made for the better.

Getting sober in 2008 is by far the best decision I’ve ever made, because every other good thing came out of it. Without sobriety, I would not be able to mother, create, be a partner, or a friend. Alcohol only took, never gave. Alcoholism is one of the most brutal diseases. I think if you haven’t seen it up close maybe it’s hard to understand, but I saw it up close in my family from my earliest memories, and saw it culminate in horrific alcoholic deaths, so I have a very clear idea about what it can do. I knew the only way to truly create generational change would be to stop completely. Since then, I’ve gotten to show up as myself now for almost seventeen years. I can hear my intuition, and more than anything, it created a strong trust muscle in me that I can do whatever I set my mind to. I will never regret not drinking. In the same way I’ll never regret reading more, or writing more, or spending time with the ones I love. It’s one of the foundational things about me, and really feels redemptive. In the beginning I didn’t always talk about it because there was so much judgement, but then I realized that it’s my duty to show others that an alcohol-free life is possible, joyous, and amazing. I know it's expanded people because they’ve told me, and that’s the best gift, getting a DM that says, “hey, so I’m a week sober!...” The power in people sharing their stories cannot be underestimated.

Tell us about your new book, Madwoman.

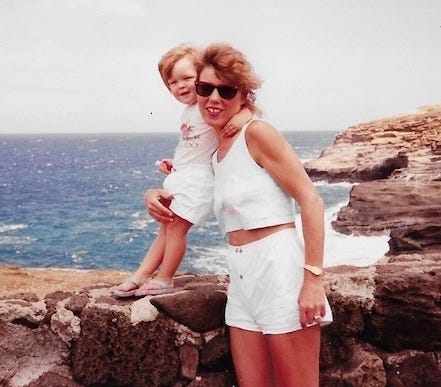

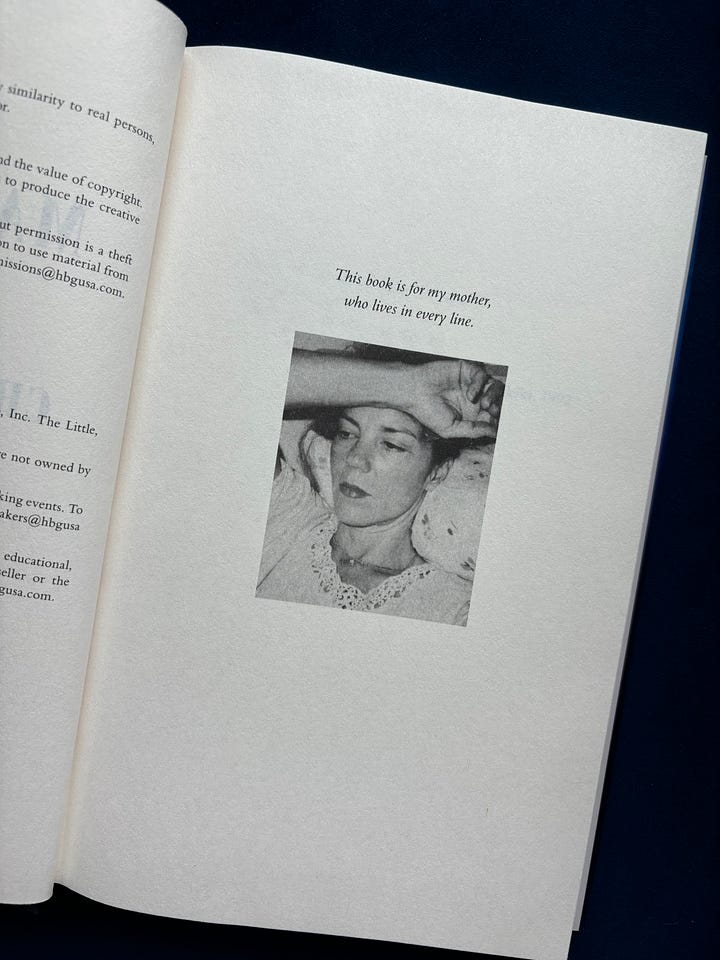

Madwoman is dedicated to my mom who died two years ago. I had the wildest experience writing this novel, where I’d call her and describe a new scene I’d written (she was always asking, what happens next?!) and I would think I’d totally made it up, and she would be like, “oh yeah, that really happened.” I was accessing memories from a very young age not totally realizing it, and then she would give me the run down on what had actually happened. I am not surprised by this; I think so much of what we write comes from those deep subconscious places but I feel grateful her and I had moments like that where the alchemy of both of our days hit right and we could really, really connect. Those moments were super hard to come by, but there was something unifying in talking about the book.

Here’s the thing: I write so much about how difficult my relationship with her was, and believe me, loving her was and is incredibly painful, but actually the core of the relationship itself was awesome. She was so damn funny and smart and one of the most expressively loving people I’ve ever met. It is hands down because of her that I can be effusively affirmative to my children, no holds barred, just so enthusiastic with them, because she offered that to me.

So, the relationship was fine, it was everything that stood in the way of it that was problematic. Yeah, some things she placed there herself, and then the things that came from outside (violent men). I mean, that opens up a whole other topic, but the fact that even though my mom’s abusive partner was apt to walk in at any moment and interrupt her meager phone time with me—we still had our moments despite him. I’m here for women reclaiming space, narrative, and time. The women in my family who have been diminished by men…I mean this is the most serious sense—my aunt was literally murdered by her ex-husband—and then others spiritually killed. When my mom died, the coroner’s report said she died of “complications of alcoholism.” When I saw that, I remember something felt off to me, even though nearly her entire life was marked by addiction. I thought to myself, no, that could be truer: she died of complications of domestic violence. So that’s the sort of spiritual imprint of the book.

In story terms, Madwoman is a novel that follows Clove, a mother of two young kids in Portland, Oregon. She has a pretty great life with a loving, safe partner. Sure, there’s her secret mounting credit card debt, undiagnosed post-weaning anxiety disorder, and the fact that no one, not even her husband, knows who she really is, or the truth of her past. When she receives a letter from a women’s prison in California, shit goes sideways, and her past comes back to her. Essentially, it’s about facing the darkest parts of yourself to finally be free; how to mother when you haven’t been mothered yourself; how violence invades women’s relationships with each other.

In the beginning I thought I was writing a darkly funny book about wellness culture and motherhood, and I quickly realized I was writing a much deeper exploration of the long-term effects of domestic abuse, escape, and what healing really looks like. Spoiler—there’s no amount of green juice and supplement in the world that can help you avoid looking squarely at your darkest places! I wanted to write a book about women who were hell-bent on surviving, and not just that, thriving. The women of Madwoman are not merely victims—they are full bodied individuals navigating friendships, falling in love, mothering, hating small talk, navigating aging, and all the rest. It’s about owning your story so it doesn’t own you. I hope it sparks conversations and healing for readers.

Tell us about a regret you have or a mistake you’ve made.

In the powerful book on aging and death, Being Mortal, by the physician Atul Gawande, he opens with an anecdote from The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Tolstoy’s classic novella. In it, Ivan lies on his death bed as the people around him remain convinced he is not dying, but instead merely ill, focusing on his treatment, and upholding the vague idea that if they just do all they can, something it will all turn around. But Ivan knows he is dying and he is scared. Yet no one around him will acknowledge his impending death, ill-equipped to handle death themselves. He longs to be pitied and petted and comforted like a “sick child.” He longs for them to stop what they are doing, and simply witness and acknowledge this phase that awaits us all.

I wish I’d read this book before my father began to decline, before he was very obviously (or should have been obvious) dying. My last conversation with him was over the phone in the early part of the pandemic. His voice was nearly gone. I remember saying, “When you get better, dad, we’ll take you to Hawaii. Something nice.” He agreed to that, and we hung up shortly after. But I so regret this.

While logically I can have compassion for myself in that moment—a mother of two children under age six in lockdown, exhausted in a thousand ways—I was holding on to the hope he would get better. But didn’t I know he wouldn’t? I’m not sure some days. Maybe it was all too much. I wish, I wish, I wish. I wish I’d gotten in my car and driven to him. Pushed past all the fear of making that long journey through the gorge in the middle of icy winter, my fear of infecting him with covid, or him infecting me. So many barriers. But at the very least, I regret not acknowledging that he was dying. How alone he must have been. His daughter mentioning Hawaii as if that could be true. I wish I had said, “dad, I know you are dying. Dad, I love you so much. How does it feel for you? What can I do for you, or say in this moment?” Something. Anything. I wish I’d never hung up the phone.

But my father and I had never talked about death before. He wouldn’t. Not even after all the close calls he’d had in his lifetime. He wasn’t capable, and I knew so little about it really, because no one had ever talked about it with me. Death, always pushed to the side of things. I wish I could have held his hands as he died, and just been with him for that. Just witnessed him in that moment. People try to convince me out of this, probably because they can see the things I can’t—how hard I tried in other ways, how much I advocated for him with his doctors, all the calls, all the work, all the nervous system devastation. A few months ago, expressing this regret, a wise body worker reminded me that logic has no place when it comes to grief. “Forget logic!” she said. “You are feeling this and that’s all that needs to be known. We work with feeling.” So I feel regret. I live with regret. The only thing I am at peace with is the fact of this regret’s presence. Absolution of it might not even be the goal, but a softening that only time can offer.

Tell us your best advice.

My best advice is to find a way to love yourself. Really love yourself, every stage and every age. When I started doing Internal Family Systems work (IFS) which essentially is acknowledging you are a Self made up of many Parts, and these Parts are formed in childhood in our traumatic moments and operate in the now with the intent to keep us “safe” but likely cause more harm than good. Doing the work of getting to know my Parts and reassigning them has been one of the most therapeutically helpful things I’ve ever done. They just need to be heard and seen and soothed. I realized there were parts of me I really did not want to acknowledge or felt ashamed of, and learning to love these more shadowy parts has been hugely transformative and healing.

I do think for a long time I thought I could bypass self-love and focus instead on outward success, and that eventually the outward success would equal self-love, or rather, the success would allow me to finally really love myself. But it’s not true. For so many reasons this is faulty thinking, but I just didn’t want to look at it. I think once I finally surrendered to the idea that the Work would be to actually love myself no matter what success I achieved or didn’t achieve, things really opened up in new ways for me. I could hold everything more loosely. If I really value myself and believe in my own inherent worth, then things like a bad review, or not getting x y z can just roll right off me. But there was a time when rejection felt devastating, like proof that I’d never be good enough. I think that’s what happens when you’re looking for parental love in all the wrong places, but I would tell anyone that building that unshakable love and trust in yourself is paramount. I like to practice it in lots of ways, but one way is literally recording kind affirmations to myself in my phone and listening back to them, as if I’m talking to the sweetest child, how I’d talk to my own children. Because I am talking to a sweet child! We’re all sweet, lovable, children but it can be so hard to believe that truly. It takes some repetitive work to feel the changes there.

Chelsea Bieker is the author of two novels: Madwoman, released on September 3, 2024, and the national indie bestseller, Godshot, which was longlisted for The Center For Fiction’s First Novel Prize and named a Barnes and Noble Pick of the Month. Her story collection, Heartbroke won the California Book Award and was a New York Times “Best California Book of 2022” and an NPR Best Book of the Year. Her writing has appeared in The Paris Review, Granta, The Cut, Wall Street Journal, McSweeney’s, and others. She is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Writers’ Award, as well as residencies from MacDowell and Tin House. Raised in Hawai’i and California, she now lives in Portland, Oregon with her husband and two children.

I put Madwoman on my list. I resonate so strongly with everything she said, about caring for and loving your inner child in order to show up today.

And this:

"I thought to myself, no, that could be truer: she died of complications of domestic violence."

We don't understand or talk about this enough as a society. The effects of DV drive us to do things that make us look insane to the outside, which in turn allows our abusers to say we are "crazy" or "unwell." I'm two years into recovery from leaving a violent family situation and I'm still working to validate my sanity every day after 40 years of being told I was unwell.

Powerful and well written. Thank you for introducing Chelsea Bieker, her books, her Substack, and her relationship with you. Two solid pieces of wisdom in your interview and the older you get, the greater the value of both: 1) Learn to love yourself, unconditionally, every stage and every age and 2) Learn about aging and death as soon as you can because when it's your turn to walk the aisle with your dying mate, you need to understand the dying process and how scared they are.